The Stories She May Not Tell You

Women-founded companies still only attract a tiny fraction of venture capital cash.

Two weeks ago, I caught up with a dear friend. I’ll call her J.

J and I hadn’t spoken for a while—perhaps since the weird and woozy days of the early pandemic—but we’d kept up to date on each other’s lives, at least to the somewhat superficial extent that social media permitted.

I admire J tremendously. Some years ago, she’d quit her job as a banker and turned her passion into a profession: she’d launched her own company, a women’s workwear brand dedicated to clothing that consistently empowers and never restricts. Her pants and jackets have pockets that actually fit phones and wallets rather than just chapsticks and bobby pins. The waistbands don’t pinch. The fabric is easy to wash and dry, because—let’s be honest—who the hell ever has time to iron anything anyway?

J’s products aren’t cheap but they are of undeniable quality. And most importantly, when I wear them I feel like I’m supporting a company and a business leader who truly cares about gender equity in society, the economy and further afield. Her pieces also make me feel put-together. I don’t spend much money on designer items, but wearing her brand, I feel a little bit fancy. These items are like armor; an extra membrane of otherwise invisible confidence. I never thought I’d care this much about fashion. Turns out I do.

Over the years, I’ve worn J’s clothes to important interviews and meetings—occasions where I’ve wanted to feel assertive and comfortable—on stage and on TV; I’ve coupled them with pajamas bottoms on high-stakes Zoom meetings. That first in-person meeting after months of Covid-necessitated social distancing? J designed the shirt. If she hadn’t, I would’ve had no idea what to wear.

I called her recently because I’d heard some news that had shocked and saddened me. J had reached the difficult decision to close up shop. Despite the brand sporting a loyal client base that had grown steadily over the past seven years, operating had become financially unsustainable and irresponsible. Funding had dried up; more specifically, funding in a way that didn’t compromise the ethos of her organization—her fierce and unflinching commitment to sustainability—had evaporated.

Now J’s in the final days of sales. Every time I get another e-mail announcing a fresh discount on one of her products, I experience twin pangs of emotion: glee at the prospect of getting a beautiful item of clothing at cut-price, and sorrow that a brand with such an admirable mission and such unyielding, deeply-rooted core values couldn’t withstand the adverse headwinds. The relentless forces of capitalism famously know no mercy. I’ve ordered one last pair of pocketed, comfortable-but-very-chic trousers and one last black shirt that will go with anything. I’m hoping they’ll see me through the next few years of professional milestones and challenges.

J’s story makes me sad for many reasons. On a personal note, she’s my friend. I had seen her infuse this brand with so much energy, passion, and commitment during a period of personal upheaval, not to mention a global pandemic. Launching a business, propelling yourself off the cliff of predictability and into the utter unknown, is almost always admirable. But when the entrepreneur doing it happens to be your friend, you just feel another level of awe. Although what’s ultimately happened to J could never be construed as failure, I’m disappointed that, over this past year, she’s had to make decisions on account of factors that were so far beyond her control: macroeconomic headwinds, the market for raising venture capital, and consumer appetites spoiled by a raging cost of living crisis.

The other reason what happened to J makes me sad, is that what she endured—the headwinds that J the CEO encountered—is something that will feel familiar to so many other women. She was unable to get the buy-in, the financial backing, that many other entrepreneurs have been able secure. Of course I can’t speak to the reasons why some investors didn’t choose to give her the money and resources she would have needed to keep on going. Obviously, every founder’s story is different, just as every decision to discontinue operating is informed by different dynamics and circumstances. But I can’t help think of the absolutely gigantic difference between the amount of investment money that female-founded start-ups attract versus male-founded ones, and the options, opportunities, and freedoms that come with that extra support.

As I write in my upcoming book, U.S. start-ups founded by women alone raised nearly 6.4 billion dollars of venture funding in 2021, representing an impressive 83 percent rise on the previous year’s figure, according to data group PitchBook. But there’s a bleaker story here. Despite that sizable jump, companies founded solely by women garnered just 2 percent of all dollars invested in venture-capitalist-backed start-ups in the United States. That’s nothing short of damning.

The reasons for this gaping divide are numerous. Unconscious and conscious bias certainly play a part. But based on many, many interviews that I did while working on the book, I’ve concluded that the overarching climate in the world of raising money is also just extremely male and frequently toxic. It is a thriving, but not fully-appreciated, vestige of the age-old boys club.

The women I’ve spoken to about this describe it in different ways. One said that a male VC partner asked her repeatedly about her husband’s career in a conversation that was ostensibly about her business’s potential for success, a business, to be clear, in which her husband played no formal role whatsoever. Her interpretation? “He wanted to know if my husband was rich and smart enough to bail me out if I screwed up.”

Other women have told me about the questions they’re forced to field that relate to family: “Do you have kids?” or “Do you have plans to start a family?” The subtext here, of course—and these are my words, not their—is “are you about to go on maternity leave, abandon your business and render my investment a colossal waste of money?”

There are also the unwanted advances and assaults that female founders have to endure in their impossible quest to achieve the same degree of respect and acceptance as their male counterparts. As I write in the book, “anywhere there are female founders and VC money, there are whispered stories of women being touched inappropriately, propositioned, and maligned and insulted when a sexual advance is rebuffed.”

And quite quickly, it becomes very easy to see how for many female founders the pressure to raise capital and to sustain a financially viable business becomes intolerable when overlaid with a culture of rampant misogyny that blatantly disrespects them.

Entrepreneurialism is a core tenet of the American Dream. But as I conclude in my book, the American way—and the way of many other economies outside of the United States—is also to look away from painful realities when it’s convenient to do so; for example, to ignore the fact that it’s often impossible for a founder to reach her professional potential if she’s not of a certain gender.

A few days after my last conversation with J, I was invited to a lunch where I happened to meet a male entrepreneur. His tech company had just completed a round of funding and he almost seemed to glow as he told me that, contrary to what I might’ve been hearing, the funding market was wide open for business. “Last week”—he went on—“a friend of mine got $15 million from a major investor. It’s weird because he hasn’t even really got an idea. Just told his funders he was working on something to do with AI.”

The currency of confidence—when displayed by the right person, in the right context—is remarkable. And nonetheless, I am so encouraged by people like J, by female founders who persist and persevere, by those who single-mindedly commit to their core values, despite the discouraging statistics, the sickening stories, and the risk of having to make a decision that really hurts. There are those who defy the data, and every woman who claims her rightful place in a pitch meeting is helping to chip away at that incessant norm; that frankly ridiculous belief that women, money, and power just shouldn’t go together.

WOMEN MONEY POWER: The Book

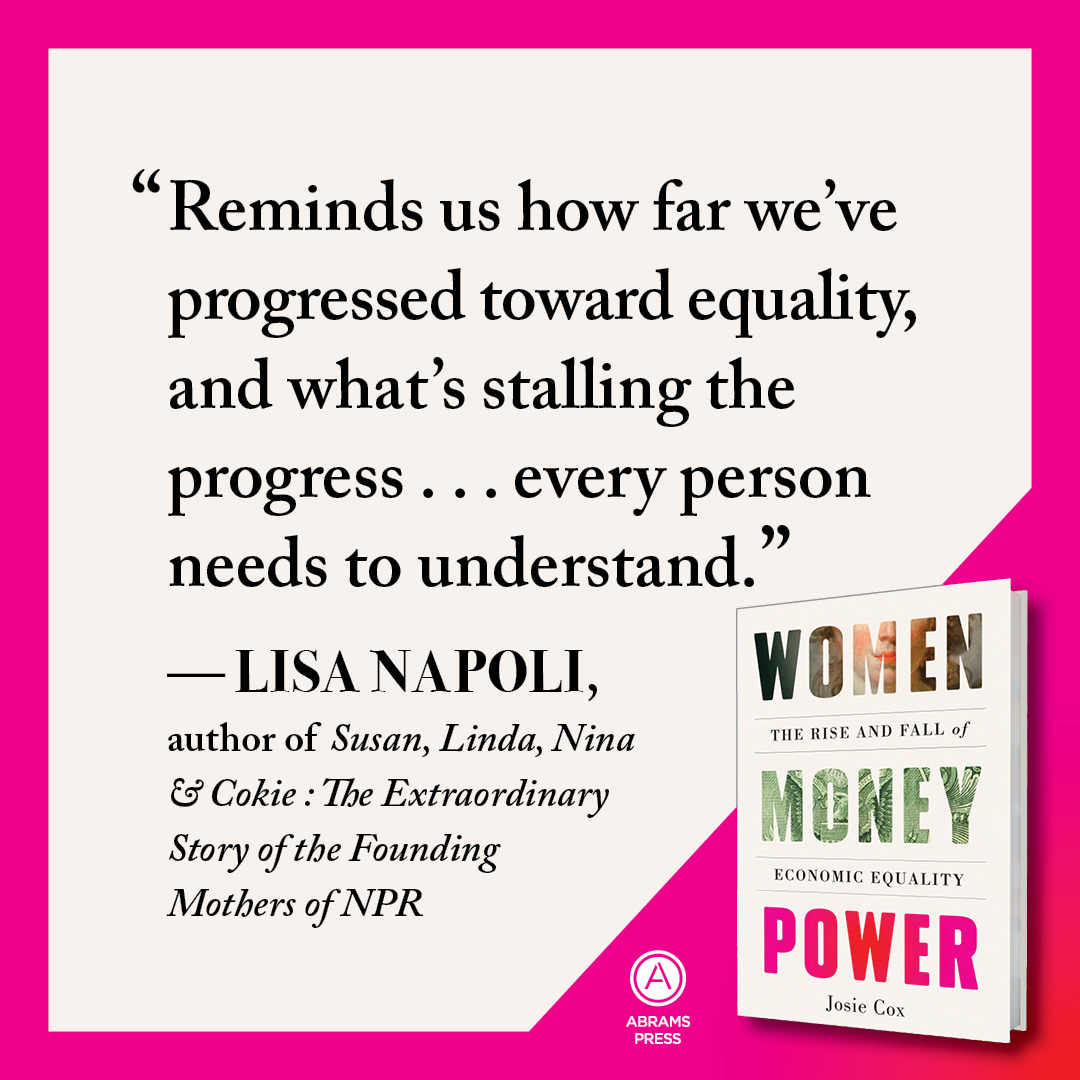

As always, a quick plug and update on WOMEN MONEY POWER, the book, which is out on March 5. In case you missed it, I recently got some gorgeous graphics from my publisher, including this one.

I’ve said it before and I’ll said it again: everything you’ve been told about pre-orders is true: they’re extremely important for any book, and they can hugely influence chances of making bestseller lists, which of course, is a big deal. All of that is to say, if you like what you’ve been reading here, if you care about female economic empowerment, if you—as a champion of gender equality—want to learn more about the giants upon whose shoulders we (often unknowingly) stand, then please consider putting in your order.

You can do so through my publisher’s website here, Barnes & Noble here, Bookshop.org here, Thriftbooks here. Other retailers are, of course, available and get in touch if you’re ordering from abroad or if you’d like a discount for bulk orders.

Please get in touch if you’re interested in collaborating or booking me for a speaking gig. I’d love to visit your local bookstore, company, school, campus, affinity group, or other event. I can’t wait to share what I feel like I’ve spent my entire life working on!