A Fertility Revolutionary You've Never Heard Of

Scientist Robert Edwards and gynecologist Patrick Steptoe are widely credited with conceiving the first 'test tube baby' who turns forty-five next week. Their success was dependent on Jean Purdy.

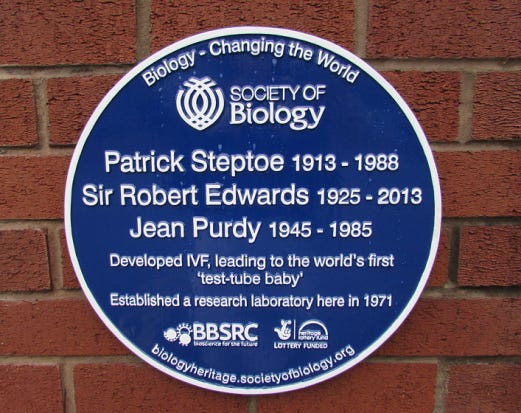

Image courtesy of Royal Society of Biology.

Next Tuesday, Louise Brown will turn forty-five.

When Brown, who lives in the U.K., was four years old, her parents showed her a video of her birth—a c-section delivery—and explained that she was born in a slightly different way to everyone else.

Indeed, rather than being conceived in her mother’s fallopian tubes (where fertilization of an egg typically occurs in humans), she was conceived in a jar that’s today housed at London’s Science Museum. Brown was the world’s first test-tube baby, though personally she prefers the term “IVF” baby, since there weren’t actually any test tubes involved, she told TIME magazine on her fortieth birthday in 2018.

Her birth was certainly one of the most anticipated in modern history. Scientist Robert Edwards and gynecologist Patrick Steptoe had been working on the concept of human IVF for about a decade before Brown took her first breath.

In 1969, Edwards had first fertilized an egg outside of the womb at which point he began collaborating with Steptoe. The pair started working to refine their technique for humans, drawing on the help of Jean Purdy.

In a tale as old as time, Purdy has almost entirely be written out of history books. She was, in fact, a revolutionary embryologist and has been credited with being the first person ever to recognize and describe the formation of the early human blastocyst: the rapidly dividing ball of cells that forms about five or six days after fertilization.

In a 2017 paper, physiologist Roger Gosden describes Purdy as an unlikely pioneer. “She qualified as a nurse but through indefatigable effort and unstinting loyalty to a program that faced vitriolic opposition she became the clinical embryologist for the first IVF baby,” he writes. “Although Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe generously credited her role in research and clinical care, a premature death in 1985 at age thirty-nine robbed her of the reward of witnessing the blossoming of assisted reproductive technologies for patients around the world,” he adds.

Other don’t quite buy the fact that it was her early death that led to her relative obscurity.

“This is probably only part of the reason,” writes Connie Orbach, who curated an exhibition on IVF a few years ago, in a blog for the Science Museum. “Patrick Steptoe died in 1988, soon after Purdy but also long before the Nobel Prize that was awarded to Robert Edwards for the work in 2010. Steptoe’s name does not seem to have been lost to the passage of time.”

Orbach writes that Purdy was based in Cambridge, and frequently drove the hundreds of miles to their clinic in Oldham, which is in Greater Manchester, taking her away from home for several days at a time. “Purdy was so indispensable,” Orbach explains, “that when she was unable to travel while caring for her ailing mother, all work stopped for several months.”

Whatever the reason why Purdy’s name is often not mentioned in the same breath as Steptoe and Edwards, it wasn’t because Edwards didn’t want her to be. “He repeatedly emphasized Purdy’s importance and unsuccessfully lobbied her name to be added to the commemorative plaque placed at the site of their original clinic,” Orbach explains.

Finally, in 2015, Purdy’s name was added to the plaque. At the unveiling ceremony, Louise Brown made a statement. “My mum always spoke with great affection of her visits to the little cottage hospital in Oldham where the biologists did such great work,” she said. “It was here Jean Purdy first saw cells divide through a microscope— the beginning of my life!”

Happy birthday Louise Brown. And here’s to you, Jean Purdy. May your well-deserved legacy grow with the advances we make in thr extremely important field of reproductive science.

World Cup Kick-Off

Elsewhere this week, the 2023 Women’s FIFA World Cup kicked off. Earlier this month I wrote about my investigation into pay in women’s soccer that I did some years ago, but inevitably on this topic, there’s always more to say.

CNN this past week published an article crunching the numbers afresh and establishing that players at the tournament this year will, on average, earn just 25 cents for every dollar earned by the men at their World Cup last year.

Yes, that’s grim. But it more mark an improvement of sorts. Back in 2019, it was less than eight cents per dollar, according to data provided by world governing body FIFA and global players’ union FIFPRO, as reported by CNN.

CNN reached out to FIFA for comment on the gap as it stands today and was referred to what FIFA President Gianni Infantino said in March when the organization unveiled details of the prize money that would be on offer at this year’s tournament.

He said that FIFA was embarking on a “historic journey for women’s football and for equality. He added that the aim was equality in payments for the men’s and women’s World Cups in 2026 and 2027 respectively.

Rest in Peace, Martha Saxton

And finally this week, Martha Saxton, a historian who wrote extensively about the lives of figures ranging from the author Louisa May Alcott to Mary Washington (George Washington’s mother), died on Tuesday at her home in Norfolk, Connecticut. She was seventy-seven. The cause of her death—according to her daughter—was lung cancer.

Here’s an excerpt from Clay Risen’s obituary for the New York Times:

“First as a freelance writer and later as an assistant professor of history and women’s studies at Amherst College, Professor Saxton excavated women’s lives from under the morass of male privilege set down both at her subjects’ time and by historians over the intervening years.”

And in a 2019 book that Saxton published about Mary Washington, she herself wrote this:

“I have spent my life studying and writing North American women’s history to try to retrieve some of what has been lost, to try to replace incomprehension or criticism with historical context, and to substitute evidence for stereotypes and sentiment.”

Personally, I love the idea of substituting evidence for stereotypes and sentiment and think it’s something we should all strive to do.

Risen writes that at the time of her death Saxton was nearing completion of a biography of the 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon. All that was missing was a final chapter. The author Judith Thurman, who was a close friend of Saxton’s, and Amrita Basu, a professor at Amherst College, have said they would finish the draft.

Thank you for reading! As ever, comments, questions and criticism are always welcome. And please feel free to share this newsletter with others who you think might enjoy it.